Overview

Within This Page

For many historic structures, building systems are new additions that must be incorporated with as much sensitivity to the original fabric as possible.

Careful planning is required to balance preservation objectives with interior systems, such as HVAC, electrical, plumbing, structural systems, information and communication technologies, and conveyance systems. Since new mechanical and other related systems, such as electrical and fire suppression, can use up to 10% of a building's square footage and 30%–40% of an overall rehabilitation budget, decisions must be made in a systematic and coordinated manner. While it might not be possible to always completely conceal the presence of new technology, it may be possible to lessen the impact on a building's integrity and retain as much of the original building fabric as possible.

Exposed spiral ductwork is appropriate in this industrial interior. This treatment is not appropriate in more finished interiors, where plaster covers walls and ceilings. Photo Credit: National Park Service

However, more recently constructed buildings, such as early 20th century commercial buildings, may contain early systems that may be historic themselves and can be reused. For example, decorative ventilation grilles and switch plates may contribute to a building's significance as much as marble wainscoting or decorative stenciling.

The interior character of a historic building should be respected when installing new systems. For example, in a finished interior—i.e. one with plaster on the walls and ceilings, such as a house, office building, hotel or apartment building—new systems and ductwork should be concealed in attics or basements, or placed in boxed soffits. In industrial interiors—i.e. a warehouse or factory—these features may be exposed.

Changes—both big and small—can have a significant cumulative impact over time. Care must be taken during initial project design and periodic upgrades to avoid the incremental loss of integrity. Following are four basic principles to keep in mind when upgrading systems in historic properties:

Sympathetic Upgrades: Building systems upgrades should be sympathetic to the architect's specific design intent, e.g., utilitarian spaces vs. highly finished spaces.

Reversibility: Building systems upgrades should be installed to avoid damage to —or to be removable without further damaging—character-defining features and/or finishes.

Retention of Historic Fabric: "Work around" the historic fabric as much as possible. The basic mind-set prescribes forethought and respect for historic materials. For example, design systems efficiently enough to fit into existing openings or be accessible off site.

- Life-Cycle Benefit: Long-term preservation emphasizes life-cycle benefits of reusing historic properties and planning for changing needs. As such, consider the following:

- Minimize intrusions and long-term impact on historic materials as future repairs and replacements are made.

- Complex systems will require more maintenance to perform properly.

- Explore alternatives that will allow the reuse of existing system elements, e.g., reuse ducts to avoid replacement costs. Augment existing systems with digital controls and meters that can monitor performance.

- Building Automation Systems (BAS) utilize digital control devices integrated into mechanical equipment that permit the computer control of operations. Schedules for operations can be digitally set to minimize consumption. Attention must be paid to providing security as more web-enabled systems increase the risk of unwanted breech and corruption of control.

- Design zone systems that will allow repairs to be done without disrupting the entire building.

- Take advantage of financial benefits of historic properties, such as special use rental or increased rental rates, of restoring lobbies and other significant spaces previously altered.

Apartment Building, Washington, DC (late 1920's). Beam slightly elongated to accommodate sprinkler pipes and other systems in a highly ornate residential apartment building. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Early Planning

During the initial design phase, preservation zones are defined within the individual preservation management plan, giving a hierarchy of significance to the building's spaces and features (i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary spaces). An understanding of the building's most important spaces and features is critical to evaluating preservation trade-offs and preserving character-defining qualities. It is better to install new equipment in secondary or tertiary spaces, and avoid or minimize intrusions in primary architectural spaces. Basements and attics are usually good locations for horizontal routing of systems; existing chases such as fireplaces, flues, and utility closets are good for vertical routing of systems; and use existing penetrations and chases to the greatest extent possible. Also, janitorial closets can be good locations for electrical equipment. Where possible, use this opportunity to improve on the placement and function of a building's systems so as to emphasize the building's integrity.

Be aware that some basements may themselves be historically significant because of prior use, storage, or other factors, not necessarily related specifically to the building containing the basement. Also basements excavated prior to the NHPA might have intruded into significant archaeological sites, so ground disturbances due to new utility trenches, exterior waterproofing, installing French drains, etc. must be subject to Section 106 consultations, either as part of the building undertaking or as separate undertakings.

Recommendations

A. HVAC—Heating, Ventilation, and Air-Conditioning

Choose a system and/or equipment that is appropriate for the use of the building. For instance, a museum has different climatic needs than an office building. Encourage collaboration between preservation specialists and design engineers to analyze potential thermal benefits of historic buildings when making systems design decisions. Consider energy modeling the historic building at the early stages of design utilizing digital software. Analysis of existing historic envelope assemblies may reveal inherent advantages modern buildings lack. In particular, mass masonry walls can provide diurnal thermal load reductions. This approach can result in a more appropriate design of mechanical systems, potentially reducing unbalanced heating and cooling. In addition, energy modeling may also show mass masonry walls that require special attention associated with modified drying potential that could result in adverse effects. It is increasingly important to develop understanding of the existing historic fabric ahead of designing to meet requirements of building rating systems and energy code requirements.

Left: Before—A dropped ceiling drastically affects the architect's original intent and grand scale of this space; and Right: After—The removal of the dropped ceiling restored the architect's intent and has a much more pleasing and commercially desirable impact. Photo Credit: National Park Service

- Retain original architectural configurations, surfaces, and finishes, such as vaulted and ornamental ceilings, pilasters, and capitals.

- Retain any existing historically significant features, such as original registers, radiators, escutcheons, radiator enclosures, etc., by reusing existing ductwork, vents/air intakes, and janitorial closets.

- If disturbance is unavoidable, the replacement should match the design, color, texture, and materials of the original.

- Match the finished appearance of the space to the original.

- Ensure that the addition of HVAC systems and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

- Select systems that are compatible with historic fabric to the maximum extent. For example. Instead of extensive duct work, consider routing refrigerant lines to local equipment such as Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) systems to console units. Units can be concealed individually minimizing long exposure runs of ductwork. Where radiant heating systems are being upgraded to modern HVAC, indoor floor-mounted VRF units can be concealed in (existing) compatible radiator enclosures. System design must ensure condensate drain piping is discretely integrated.

- Give careful consideration to the introduction of humidification systems into historic buildings. Adding humidification can damage building envelopes without perfectly sealed vapor barriers, which are difficult to achieve in existing buildings. Uses such as museums in historic structures often find themselves in conflict between the needs of occupancy versus the capability of the building to achieve desired environmental conditions. The New Orleans Charter is one document that describes the challenge and provides some guiding principles in meeting the needs of museum collections in historic buildings. Even the introduction of other new uses in structures not originally designed for tight envelopes and environmental controls, such as barns, can cause damage to building envelope and structure if not carefully done.

In this large apartment complex in Washington, DC they used a "split ductless" HVAC system. The only evidence of this mechanical installation are small, simple indoor air handlers in apartments (mounted on walls—a different type of unit is used for ceilings—not shown here) and small condenser units placed on rear balconies that face a utilitarian courtyard. This system is relatively expensive, but it has limited physical or visual impact on the historic interior or exterior because ii requires no ducts.

Another example of a "split ductless" HVAC system air handler inside of a mill.

Distribution System

To preserve the distinctive decorative pressed-tin ceiling on the interior of this finished late 19th-century commercial building, spiral duct work was left exposed. This approach was taken because in this instance, it would be more intrusive to add a boxed soffit. The exposed duct was painted the color of the walls to lessen its impact. Depending on the circumstances, painting the duct the color of the ceiling may work as well. It was also placed at the perimeter of the room, so the important open retail space was not subdivided, and was installed close to the ceiling, so this new feature does not appear more prominent as it hangs down. This solution meets the Secretary's Standards. Photo Credit: Audrey Tepper

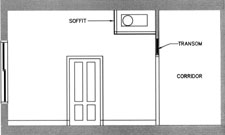

Ductwork retrofit. The insensitively installed ductwork detracts from the hallway's scale and obscures the transoms. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Avoid the need for new ductwork, especially in lobbies, corridors, and other circulation spaces, by examining ductless alternatives such as split systems and pipe systems with reuse of existing ducts for ventilation.

Avoid lowering ceilings in significant spaces. If new ductwork is unavoidable, disturb as little original fabric as possible and minimize the visual impact.

Avoid reconfiguring ceilings (e.g. suspended ceilings) to accommodate air distribution.

Install in secondary spaces such as attics or basements first. If service areas are not available, carefully place in secondary areas, never in primary spaces, away from window heads.

Retain full window height so that exterior appearance is unaltered.

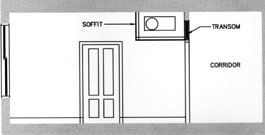

Configure ceilings to avoid obscuring the full height of windows and interior or exterior transoms.

Retain decorative millwork and other character-defining features. Rather than puncturing decorative elements, move the position of the ductwork.

Configure ductwork to be as flat as possible and to avoid disrupting the symmetry of the space. Explore zoning using multiple, smaller ducts, rather than a single, larger profile duct system.

Avoid running ductwork along or across corridors.

Where appropriate, step, slope or pocket out the ceiling with sufficient depth to retain the original appearance of a full, un-obscured window from the exterior.

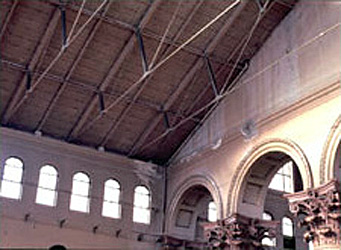

In some cases, exposed ductwork may be appropriate, such as in industrial or other utilitarian buildings, or spaces with vaulted or other decorative ceilings that would otherwise have to be obscured.

A good example of ductwork installation does not lower ceilings in public corridors or obscure windows or transoms. Photo Credit: National Park Service

A bad example of ductwork installation obscures either windows or transoms or both. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Building Envelope

Former bank building (now a hotel), Minneapolis, Minnesota. When an exterior wall of a building is 5' or closer to an adjacent building, fire exposure may come from either the inside or the outside of the two buildings. Therefore, fire separation in some form must be provided. In order to retain the window opening, rather than infilling to achieve code compliance, a sprinkler head was installed at the window to ensure proper safety. Photo Credit: National Park Service

- Retain window operability; install locks and/or stops if required to control tenant use.

- Use operable windows for natural ventilation during temperate spring and fall months whenever possible.

- Use weather stripping and insulating doors and windows, instead of replacing or sealing windows.

- Consider the architect's original energy conservation methods, such as operable windows, porches, overhangs, etc. Incorporate these features into the overall energy conservation plan.

- Are weather stripping and storm windows appropriate?

- Retain original ventilation systems, (e.g. attic vents, crawl space, and airflow patterns).

- Carefully consider insulation options; ensure that the chosen method/materials will not create condensation in a building's interior.

- In certain climactic conditions, a vapor retarder may reduce the moisture contribution from interior spaces. However, in well insulated walls during cold weather the benefits may, in fact, be small. According to the NPS Brief No.3, Vapor Retarders must be continuous to work properly, which is often difficult in existing buildings. Also, if moisture moves from both the interior and exterior, depending on the season, a vapor retarder may not be required (DOE Insulation Fact Sheet, pg. 14).

- Maintain good breathability/permeability of the envelope; be mindful of the original structure's inherent tolerance to moisture.

- Cost Benefit Analysis

The major renovation of The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum preserves and respects the historic character and building envelope of the National Historic Landmark building, while modernizing infrastructure and systems with state-of-the-art sustainable and energy-efficient technologies. The renovation also included restoration of many of the building's historic details and installation of new blast-resistant windows. Photos by Kevin G. Reeves; Courtesy of Westlake Reed Leskosky (now DLR Group). To see the entire case study, click here: The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Basement Mechanical Room after restoration. Color coding of all piping jacketing allows greater clarity for system maintenance. The air-handling unit incorporates a six-fan array and was assembled in place over a three-week period. Photos by Kevin G. Reeves; Courtesy of Westlake Reed Leskosky (now DLR Group). To see the entire case study, click here: The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Equipment

- Install air handlers and other equipment in locations that will least affect building occupants and activities (e.g. vibration and noise).

- Install wall or ceiling mounted equipment in secondary or tertiary spaces.

- Locate any exterior building equipment adjacent to a secondary or tertiary façade or landscape, rather than the primary façade or landscape.

- Landscaping is a low cost method of camouflaging new HVAC equipment.

- Remotely locating new equipment may be necessary if there are archeological or historic landscape features immediately adjacent to a building.

- Hide roof-mounted equipment from the street or other obvious vantage points (a site study can indicate good locations).

- A detailed discussion of installing HVAC equipment in historic buildings can be found in Preservation Brief 24: Heating, Ventilating, and Cooling Historic Buildings Problems and Recommended ApproachesDownload preservation-brief-24-heating-cooling.pdf .

The sensitive placement of new mechanical equipment on the exterior of historic buildings is very important. Highly visible components not only adversely impact the character of the building itself, but also the surrounding site and environment - often a historic district. New utilities should be designed to be as small as possible and be located in secondary areas with limited visibility. These installations do not meet the Secretary's Standards. Photo Credit: Audrey Tepper

Care must be taken in historic interiors—especially those that are highly-ornamented—to place utilities in locations that avoid impacting historic fabric. These examples do not meet the Secretary's Standards. Photo Credit: Audrey Tepper

B. Information and Communication Technology

Information technology (IT) systems are complex and constantly changing. These systems have exponentially increased the need for easily accessible wiring raceways. Today's modern office buildings incorporate raised floors that allow easy access to wiring systems. Although not appropriate for all buildings and spaces, in some historic buildings this approach can enable retention of ornamental ceilings and features. Wireless IT systems enable historic buildings to meet changing needs and workspace standards with less impact than is required to route wiring through architecturally significant interiors. Space reservation systems support shared use of meeting spaces, mobile workspace, and other efficiencies that contribute to the sustainable reuse of historic buildings in urban areas and costly real estate markets.

- Consider wireless solutions.

- Reuse existing conduit and wiring chases to the greatest extent possible.

- For small and/or highly significant buildings, consider locating computer servers off-site.

- Design for flexibility of layout.

- Install computer and IT wiring and routers for Wifi that can easily be reversed.

- Ensure that the wiring and associated equipment are easily accessible so that they may be periodically replaced and updated.

- Ensure that the addition of information and communication technologies and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

Computer Rooms

- Locate servers in appropriate climate-controlled tertiary spaces that minimize intrusion, such as basements or existing windowless rooms.

- Avoid altering doors and windows for climate control.

- Use existing vertical chases to run IT cables.

- For security, retrofit existing doors in a reversible and compatible manner instead of replacing them.

Wiring Distribution

- Retain decorative millwork and other character-defining features.

- Avoid obscuring or altering decorative cornice and other character-defining features.

- For ornamental spaces, consider raceways hidden by historic cornices and moldings.

- Do not install exposed wiring systems.

- Create a maintenance plan with strict standards for installation of new wiring and equipment. Ensure that copies of wiring diagrams are available to building managers and external locations.

- Design for flexibility and expansion.

- Do not drill marble, parquet, terrazzo, and other finished flooring. If unavoidable, drill in corners to minimize impacts and run wiring along baseboards.

- Select high-quality, highest speed, and smallest size cabling to minimize the need for future intrusive replacements, especially in ornamentally significant spaces.

C. Lighting/Electrical

Historic lighting levels may not be appropriate for current or planned use of a historic building and the installation of new lighting systems may be necessary. The lighting levels and equipment should be appropriate to the building's current or planned use while respecting the original fabric.

Interior Lighting

Preserve and reuse historically significant light fixtures. This rehabilitation project reused the architect's original lighting scheme and extant fixtures. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Judge's Lamp replica Photo Credit: Jeff Jenson, General Services Administration (GSA)

- Retain as much original fabric as possible when installing new systems (i.e., do not needlessly puncture a decorative plaster ceiling or molding, when it may be as feasible to relocate a fixture or junction box).

- Retrofit existing light fixtures with reflectors to increase light output.

- Conserve and rewire existing fixtures and accessories. Even if original fixtures will not be electrified and/or used, they should be retained and preserved in situ.

- If original fixtures cannot produce the amount of light required, use alternate light sources from removable fixtures, such as task lighting and torchéres. Inconspicuous sconces or unobtrusive perimeter ceiling lighting are preferable to eye-catching modern fixtures.

- Retain and reuse original, character defining switch plates and other accessories.

- Use existing electrical chases.

- Install new chases within or behind walls or vertically in secondary or tertiary spaces.

- If using historically sensitive replacements that are wired for modern energy loads and light output.

- Replicas of original lighting fixtures can be designed to accommodate energy efficiency and multiple light sources.

- Incorporate the original light color in new lighting plans.

- Ensure that the addition of interior lighting systems and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

Limit recessed lighting to the ceiling perimeter to avoid overpowering historic chandeliers and changing the character of historic ceilings. This example is of the Edward T. Gignoux U.S. Courthouse in Portland, Maine. Image courtesy of the U.S. General Services Administration.

Exterior Lighting

- Consider landscape features when designing exterior lighting schemes; outside lighting will have implications on landscape design.

- Consider security and accessibility requirements.

- Mount on existing poles or structures.

- Install in non-intrusive areas.

- Use accent lighting as an effective way to highlight architectural features.

- Use gentle, raking light rather than large spotlights. Do not flood façades with excessive light.

- If installing exterior lighting features, such as light poles or lower light sources, choose historically appropriate options.

- Ensure that the addition of exterior lighting systems and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

D. Plumbing

Some plumbing elements such as this radiator are historic. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Prior to initiating a plumbing upgrade, it is important to ascertain whether these traditionally utilitarian spaces are in fact historic and must be preserved. If they are not historic, then rehabilitate them with sensitivity to the surrounding historic building materials, finishes, and features. However, if plumbing elements are historic, then take care to preserve them:

- Retain and preserve historically significant configuration, layout, and plumbing elements, such as bathroom and kitchen fixtures and features.

- When repairing/replacing existing pipes, do not damage adjacent finish materials, such as floor and wall tiles.

- If new pipes must be installed and are visible, they should be located inconspicuously and they should complement adjacent finishes.

- Use existing pipe runs in their original location. Otherwise, install them in closets, service rooms, and wall cavities.

- Avoid primary façades and rooms if pipes must be affixed to the interior or exterior of a building.

- Do not cut through character defining features, such as moldings, wainscoting, etc.

- Ensure that the addition of plumbing systems and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

E. Conveyance Systems

All or part of a conveyance system may be historic. For instance, this elevator cab has several character defining features, such as exotic wood paneling, elegant moldings, and metal air vents. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Elevators and escalators may also contribute to a building's historic significance. First ascertain whether these features are historically significant:

- Reuse existing components to maximum extent possible.

- Retain original fixtures, features, and materials; many historically significant conveyance systems still retain some, if not all, their original elements, particularly finish elements. Examples are original, exotic wood veneers within elevator cabs and bronze and brass switch plates, floor indicators, and handrails.

- Combine code requirements and preservation concerns; often original features can be slightly modified to meet code requirements.

- Ensure that the addition of conveyance systems and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

F. Structural

When updating a building's structure, it is preferable to retain and repair as much of the original structural system as possible. However, it may be necessary to add an entirely new structural system or to strengthen the existing system with modern innovations. For instance, a new structural system might be installed to accommodate the larger crowds associated with a museum; whereas originally, the building housed only a small family. Also, it's important to note that a structural system itself may be historic and may require sensitivity when altering or repairing it. The Brooklyn Bridge, for instance, is an example of a structural system that is inseparable from the aesthetic impact. If structural intervention is necessary:

- When structural systems have historic architectural significance; develop creative solutions to meet life/fire safety requirements as well as historic preservation goals.

- Ascertain whether the building's structure or structural components are integral to the character-defining features of the building: retain as much of the original structural form and features as possible.

- Replicate the original structural system, if necessary.

- Plan a use for the building that doesn't necessitate an augmented structural system.

- Consider the 'physics' of a proposed repair (i.e., will the alteration have the same thermal expansion coefficient as the existing structural system?).

- Carefully remove, catalogue, and store original adjacent features, finishes, and details for later re-installation. To access the structural system, it may be necessary to remove existing finish materials and temporarily number the features before reinstalling them.

- Preserve extant features of historic structural systems, such as post and beam systems and trusses.

- Sensitively reinforce structural systems; sister principle structural components rather than replace them.

- Document any structural features that are too deteriorated to retain through drawings, measurements, photographs, scans, etc.

- When selectively repairing a structural system, replace missing or deteriorated materials in-kind; examples include replicating cast iron columns.

- If substitute materials are unavoidable, they should convey the same form, design, and overall visual appearance as the historic feature. These replications should be documented.

- Use reversible repair and maintenance methods, for instance, spray in urea-formaldehyde foam would be inappropriate for a historic structural system.

- Ensure that the addition of building systems and other repairs will not corrupt the building's structural integrity.

Structural elements are an inherent part of the architect's intent; determine which parts, if any, of a building's structure are historic and rehabilitate appropriately. National Building Museum in Washington, DC. Photo Credit: National Park Service

Relevant Codes and Standards

Federal Mandates

- Code of Federal Regulations, 36 CFR 67 | "The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation"

- Code of Federal Regulations, 36 CFR 68 | "The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties"

- Code of Federal Regulations, 36 CFR 61 | "Professional Qualifications for Historic Projects"

- Executive Order 11593, "Protection and Enhancement of the Cultural Environment"

- Executive Order 13006, "Locating Federal Agencies in Historic Buildings in Historic Districts in Our Central Cities"

- Executive Order 13287, "Preserve America"Download 03-05344.pdf

- Executive Order 13834, "Efficient Federal Operations"

- National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 as amended through 1992

- National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000

For a list of other Federal Historic Preservation and cultural resource laws click here

Standards and Guidelines

- CALGreen

- NPS-28 Cultural Resource Management Guideline

- Guidelines for Federal Agency Responsibilities, Under Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act

- Guiding Principles for Sustainable Federal Buildings and Associated InstructionsDownload ceq-guiding_principles_sust_fed_bldgs-022016.pdf by The Council on Environmental Quality. Feb. 2016 .

- International Code Council

- NFPA 914 Code for Fire Protection of Historic Structures

- The Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation (As amended and annotated by the National Park Service)

Additional Resources

Publications

- Preservation Brief 24: Heating, Ventilating, and Cooling Historic Buildings Problems and Recommended ApproachesDownload preservation-brief-24-heating-cooling.pdf, National Park Service .

- Structural Analysis of Historic Buildings: Restoration, Preservation, and Adaptive Reuse Applications for Architects and Engineers by J. Stanley Rabun.

- Structural Aspects of Building Conservation (McGraw-Hill International Series in Civil Engineering) by Poul Beckmann and Robert Bowles. McGraw-Hill Text: March 1995.

- Structural Repair and Maintenance of Historical Buildings III by C.A. Brebbia and R.J.B. Frewer (Editor). Computational Mechanics May 1993.

- Technical Preservation Guidelines: HVAC Upgrades in Historic BuildingsDownload Technical%20Guide%20HVAC.pdf, U.S. General Services Administration, April 2009 .

- Technical Preservation Guidelines: Upgrading Historic Building LightingDownload TechnicalGuideLightingFINAL2.pdf, U.S. General Services Administration, April 2009 .