Introduction

Within This Page

You begin with a blank sheet. Your task is to create, from the program of requirements, within the resources available, something that works and more—something called architecture.

—From the United States Air Force's guide, Achieving Design Excellence

The act of creating architecture is indeed a wonderful opportunity to create memorable places. It is more than meeting the functional, technical, and financial criteria established at the outset. There is a more nuanced aspect to architecture that deals with aesthetics and symbolism. In every project, opportunities exist to consider aesthetic issues. Every building emerges from the ground with a particular aesthetic and that aesthetic evolves throughout the design process. Internal to the design process are countless opportunities to make aesthetic decisions, from the selection of window types to the choice of trim color. External factors can present opportunities as well, from historic preservation requirements to anti-terrorism criteria.

Description

A. Opportunities in the Design Process

The typical building process consists of at least three primary phases: 1) programming, 2) design, and 3) construction. In the programming phase, by identifying budgets, schedules, design principles, spatial requirements, and functional relationships, designers are setting the stage for aesthetic success. Low budgets and tight schedules may limit opportunities for quality design and construction. But high visibility projects may present unique opportunities for design excellence. Programming charrettes, can be especially effective in developing the principles that will guide the design effort. In a charrette, where the design team works at the client's site for a defined period of time to develop the initial design principles and concepts, the distractions of the home office are minimized and the design team can focus on the task at hand. Also, when precedents are studied and sites are analyzed, issues related to context and compatibility can influence aesthetic choices. For example, will the project be a "fabric" building thus necessitating a close fit with the existing architectural context? Or, will it be a "landmark" building that can break contextual rules related to height, materials, and proportion?

Fabric buildings create a background.

Landmark buildings stand out against the background.

Are there local guidelines or standards that can be used to enhance the design? In the design phase, when floor plans, elevations, building systems, and materials choices are finalized, designers make aesthetic choices continuously. For instance, will the windows be recessed or will they be flush with the exterior finish? Will there be any trim or details on the façade? Will there be a visible roof, a gravel stop, or a parapet?

While issues of affordability, maintainability, and constructability will naturally play a role in the decision-making process, aesthetic impacts carry considerable weight with the design team. During construction, when walls are actually built, quality workmanship plays a significant role in the final aesthetic outcome. What should be clear is the fact that aesthetics is not simply a matter of selecting colors and adding a few details to the façade. A concern for aesthetics should permeate the entire building process. The members of the design team constantly juggle issues of quality, cost, schedule, and aesthetics. Excellent designs find a balance appropriate to the project at hand.

Will the building meet the sky with grace or ineptness?

At some point in the process, when a design firm is selected a critical choice will have been made. While some owners may develop their own programs and others may select separate firms to complete the programming phase, all owners establish criteria for selection of a designer. The criteria may be as simple as a successful previous working relationship between the owner and the design firm or the criteria may fill a three page Request for Qualifications. Federal agencies must go one step further and use a transparent selection process following the Brooks Act. Fortunately, even these public agencies can select design firms not on price but on experience, qualifications, capabilities, and even previous design awards. But previous experience in working with the owner should not always be a deciding factor. For example, on a recent Air Force project, the government selected a firm that had extensive experience in the building type but no prior federal experience. The firm quickly grasped the intricacies of the federal bureaucracy and designed an award-winning project that was built under budget and ahead of schedule.

Throughout this process, the role of the owner or client cannot be discounted. As Dana Cuff found in a detailed study of architectural practice, perhaps the most significant sign as to whether a project has the potential for excellence is a client's early and appropriate demand for quality. Also, excellent projects respond to the complexity of the building process through simplicity by using streamlined operations, simplified decision-making, and an insistence on face-to-face interaction. In each case, the client plays a significant role in establishing a working relationship that leads to projects that take advantage of the aesthetic opportunities inherent in the building process. Although the client may select any number of contracting methods to execute the project (e.g. design-bid-build, design-build, fast-track), all of these methods still rely on effective programming, design, and construction to create exceptional projects.

B. Additional Opportunities

Buildings like the one shown above, with a width of only 48 feet, are ideal for office and classroom applications since the shallow footprint allows for natural light to penetrate the entire space thereby significantly reducing energy consumption required for artificial lighting.

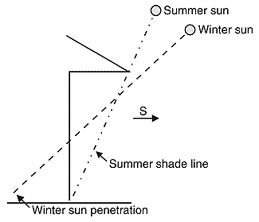

Beyond the opportunities created by the players or inherent in the design process, a wide range of issues may offer designers additional opportunities for addressing aesthetic issues. While each project is unique, some common issues that may influence the design include energy efficiency and sustainability, security design, value engineering, charrettes, operations and maintenance, public review, and historical standards. Energy efficiency and sustainable design are increasingly important to building owners and represent a significant opportunity for the designer to introduce aesthetic issues. For instance, in office buildings, artificial lighting accounts for nearly half of all energy consumption. Research at Carnegie Mellon's Center for Building Performance and Diagnostics shows that buildings with increased periphery and more glazing receive an energy benefit through daylighting and natural ventilation. The increased periphery is due to the elongated aspect ratio (e.g. 5:1) as compared to compact buildings with a smaller (e.g. 1:1) aspect ratio. Elongated buildings can have up to a 25% reduction in energy use over a similar sized compact building. According to Vivian Loftness, "The first commitment to a healthier workplace, and to environmental consciousness in the Intelligent Workplace, is the move away from large, deep floor plans with minimum window area, to a window for every workstation." Strategies that increase glazing, reduce a building's width to allow increased diffusion of natural light, and enhance shading all have aesthetic impacts.

Likewise, security design features have a clear aesthetic impact. Recommendations for increased setbacks, minimal glazing on street side façades, elimination of re-entrant corners, and elevated ground floors have aesthetic impacts that may conflict with accessibility, energy conservation, and sustainable design strategies. A careful balance is required.

Passive solar buildings allow the sun to naturally heat the interior spaces during the winter while using deep overhangs and landscaping to block the high summer sun.

Activities that may be incorporated into the design process also have a direct impact on aesthetics. For example, in a value engineering exercise, attractive overhangs, applied detailing, and recessed windows may be eliminated on the basis of having no perceived economic benefit. While the designer may have selected these items primarily on aesthetic grounds, the building may suffer in many ways because of their loss. Additionally, if not managed correctly, charrettes, which are run like intensive, on-site design studios, may raise public expectations for the project that cannot be met when the final design is completed. But charrettes are also an excellent opportunity to garner public support for a project, especially if members of the public participate in developing design principles and design ideas. Furthermore, design reviews for constructability, maintainability, and operability will flag problem items and may present an opportunity for the designers to specify higher quality, lower maintenance materials that have an aesthetic impact. For example, clad wood windows may be preferred to vinyl windows due to their potentially longer life span. Finally, historic preservation standards may force designers into using better and perhaps more attractive products that match the original character of the building. Non-conforming aluminum sliders may be replaced by more historically accurate divided light, wood casement windows. The aesthetic impact could be significant. In the end, designers should realize that every decision has an aesthetic consequence.

Application

Design challenges can be transformed into opportunities at every scale of design. At the building scale, one example is an office building at Ellsworth Air Force Base, South Dakota. The project could have been built with a maze of systems furniture, few windows, and large floor plates. But during the charrette process, it became clear that all users wanted access to natural light. Additionally, the organizations moving into the facility wanted to maintain some sense of identity. The solution was to create a building with narrow (48') wings that allowed light to penetrate across the building while, at the same time, giving each organization their own wing.

An award-winning office building at Ellsworth Air Force Base incorporates narrow wings that allow for abundant daylighting while creating an aesthetically pleasing exterior image.

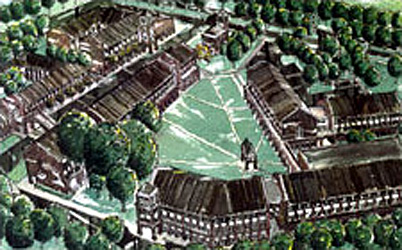

At an urban scale, an award-winning plan for a lodging and retail complex at Youngstown Air Reserve Station, Ohio used the buildings to form a campus-like setting. Rather than create one large object building, the smaller buildings create an attractive interconnected public realm.

A master plan for Youngstown Air Reserve Base in northeast Ohio used the buildings to shape "outdoor rooms" thereby recognizing the importance of integrating landscapes and buildings.

Relevant Codes and Standards

In addition to the processes discussed under aesthetic challenges, many organizations have established their own design standards and programs. For example, the General Services Administration has established a Design Excellence Program and it honors outstanding federal projects in an awards program. The National Park Service has developed standards for the treatment of historic properties. The U.S. Air Force Civil Engineer Center (AFCEC) has published Achieving Design Excellence, which outlines principles for planning, building design, and interior design. AFCEC has also published design guides for a range of building types, from maintenance facilities to office buildings and they sponsor an annual design awards program. Professional organizations, from The American Institute of Architects to the American Planning Association sponsor awards programs and provide resources for designers. Other groups, like the Society for the Advancement of Value Engineering and the International CPTED Association promote processes that impact aesthetics.

Additional Resources

Federal Agency Design Resources

- U.S. Air Force Civil Engineer Center (AFCEC)—AFCEC's Facility and Engineering Directorate - Technical Services Division is the Air Force center of expertise for architecture, interior design, facility design and construction standards and processes, and sustainability. It also sponsors an annual design awards program recognizing excellence in Air Force design and construction projects.

- Achieving Design ExcellenceDownload desingle.pdf . A brief and inspirational design guide.

- General Services Administration (GSA) has established a design excellence program to hire top-quality design firms for public projects. They also have a design awards program held every two years that honors the best federal projects. See the 2014 GSA Design Award Winners.

- National Park Service (NPS) has developed the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. These standards have been adopted by communities across the country and cover the preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction of nationally and locally designated historic structures. Access the guidelines here.

Organizations/Associations

- The American Institute of Architects (AIA)

- American Planning Association (APA)

- American Society for Aesthetics (ASA) is a scholarly organization concerned with aesthetics, philosophy of art, art theory, and art criticism. Established the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticisms.

- International CPTED Association is an advocacy group that believes that good design can lead to reduced crime and fear of crime thus improving quality of life.

- SAVE International is devoted to the advancement of the Value Engineering process in construction as well as in other fields.

Publications

- The Aesthetics of Architecture by Roger Scruton. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Architecture: The Story of Practice by Dana Cuff. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

- The British Journal of Aesthetics

- The Concise Townscape by Gordon Cullen. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1971. This book briefly summarizes Cullen's theory of "townscape," where architecture is used to give visual order and coherence to the urban environment.

- "Environmental Consciousness in the Intelligent Workplace" by Vivian Loftness, et al. NeoCon94 Proceedings. Chicago, IL: NeoCon, 1993: 20-30.

- Problem Seeking: An Architectural Programming Primer, 5th Edition by William Peña and Steven Parshall. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012.

Others

- Center for Building Performance and Diagnostics—Carnegie Mellon University. The center conducts wide-ranging research on the performance of building systems.

- National Trust for Historic Preservation—The National Trust for Historic Preservation provides resources and support in the effort to preserve and revitalize America's historic structures and communities.